The Evolution of Wings

My Answer to Nihilism

This is an unscheduled post. I felt that you should be able to read it as soon as possible.

A couple of autumns ago, I was on my daily walk through the neighborhood when I found a young crow limping in the road.

I ran home, got a burlap bag, and brought the bird home. It stayed in a plastic tub in my garage that night.

It didn’t drink, but it sat on the blankets I gave it.

The next morning I drove it to the animal rehab center. An employee sent me progress reports for the next two weeks.

Things seemed optimistic at first. The crow was alert and bright in the face. The vets suspected a systemic infection of some kind. They put the bird on pain meds and cage rest.

Further diagnostics revealed a coracoid fracture in the shoulder. The vets placed a wrap to stabilize the fracture. The crow was knuckling a foot, so the vets placed a splint and arranged further testing.

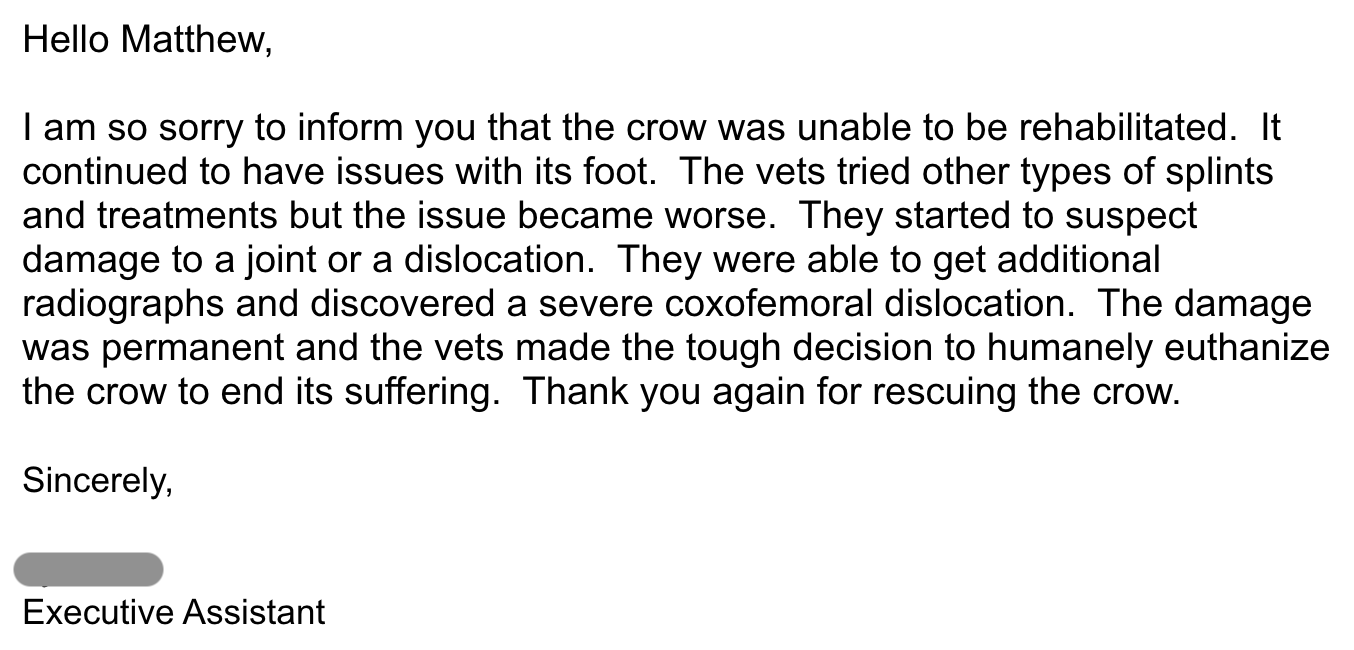

What follows is the most painful email I’ve ever received.

My contact went on to explain some details about coxofemoral luxations. She also said that, while the crow’s pain might be managed with vet care and pain medications, this was a wild animal, and such an injury would not allow the crow to survive in the wild.

I took solace in one thing. The nameless crow must have felt some comfort in its final days. It had the luxury of dying in the care of good people.

That’s more than can be said for some creatures.

The following spring, I was walking through my yard toward my driveway when a small shape fell out of the sky in front of me. It landed on the asphalt and started to scream.

It was a baby squirrel. Its fur was grown in but its eyes were still shut. I gathered my wits and rushed inside for a towel. I picked up the “kitten” (that’s what baby squirrels are called) and set it at the base of the tree it had fallen from.

I just want to preface the following with the fact that I had never thought about rescuing a baby squirrel until that evening.

I waited in the house for an hour. When I stepped back out, the baby was still by the tree, crawling blindly around the roots. I thought it might be cold, so I wrapped it in cloth and put it in a plastic bin like I had the crow. I went back inside. The mom still didn’t come. Maybe I’d put her off with my scent—or maybe she’d kicked her offspring out of the nest on purpose. In any case, time was running out, so I took the baby inside and set it under a warm lamp.

I tried to feed it Pedialyte from a syringe. Blood was bubbling from its nose. It must have hit its head pretty hard on the driveway. Its breaths grew shallow and quick. It died in my hand.

That was its whole life. A few weeks of warmth and belonging, then rushing air, a blow to the skull, and confusion—intractable pain—until death.

I’d lost loved ones before, but never suddenly or up close—not until the crow and the squirrel. They must have been the “trial version” of raw, heart-wrenching grief. One night of tears, then move on.

But I don’t really move on, do I?

Ever since I lost those two loves, I’ve been looking out for more creatures to save. I wonder why that is. I wonder why I haven’t lost hope.

The truth is, while I haven’t given up, I’ve started to question the meaning of it all.

I had a friend a few years back who was depressed and suicidal. Let’s call them X. X and I had a talk, once, about the fate we would choose for all life on Earth, should we be given the power. X said they would mercy kill every living thing on the basis that nothingness would be preferable to suffering. That was when I realized that I probably wouldn’t be able to remain friends with X.

We had that discussion before my run-ins with the crow and the squirrel, by the way.

And now that I’ve had some time to process our talk in light of those two losses, I realize that X’s beliefs must have been shaped by the creatures they’d loved—creatures like my squirrel kitten, whose short life was a blur of black and red. Why not spare them the agony? For that matter, why not spare human babies the horror of growing up in a poverty-stricken, war-torn world? These are valid questions.

Make no mistake that any answer I give is just a plate in the armor I wear. It’s my choice to move forward, despite having no blinking idea why any of this matters.

My losses have shown me a path.

I can care for other creatures. When I fail, I can learn. Maybe someday I’ll be prepared enough to make a difference for a creature in need. Or maybe I won’t. Maybe the payoff will come after I die.

It’s not so different from the evolution of wings.

Imagine that one little lizard, long ago, leapt five meters down the side of a sand dune.

Its offspring glided ten—the grandson, twenty.

That development took thirty years. (Just roll with the example.)

Now we have condors that cross countries without so much as flapping their wings. How long did that take?

It’s almost too much to bear—that my wishes might take ten thousand generations to come true—that my highest purpose might be to ensure that a ten-year-old girl, a million years from now, will be able to heal any wounded animal she sees with a flick of a cutting-edge rod.

Maybe I need to be okay with that.

Do I want that future for her?

Do I have that much faith in humanity?

Am I willing to swallow my pride, bend down, and let that girl stand on my back?

If the answers are yes, then I have to keep trying my best, no matter if my children, my children’s children, and my whole bloodline are stratums deep by the time their efforts pay off.

If I don’t take what small steps I can right now, my DNA might not capture those incremental improvements. My children’s arm bones could be a millimeter less wing-like. Their reflex to fly could be one percent weaker than mine.

And then we’re going backwards, aren’t we?

We simply must believe in evolution. It’s our strongest defense against Nihilism. It’s our basis for progress.

Materialism, dualism, panpsychism, idealism—I’ve entertained all the -isms. They don’t matter. I don’t need to know the nature of existence. I don’t need to know where life comes from or where it’s going. Why?

Because I see how far we’ve come.

There was a woman once, sitting over a scroll, penning her wish for a man in the future to find a limping bird or a helpless squirrel and perform a miracle.

I didn’t. The doctors couldn’t. But sometimes they do. As time rolls on, it will happen more and more—until the dying that fall in front of us are all given wings to fly.

Impossible? Maybe. But it’s the only meaning I’ve found.